The effects of Covid-19 on the Irish Property Market

The first three months of this year will go down in history as a time of extraordinary upheaval, with the spread of the Covid-19 pandemic across the world. This dislocation affected all of society and, as a consequence and almost by definition, all of the economy - here in Ireland as well as in most other countries around the world.

The pandemic has tested the policy system and underscored the importance of that elusive variable, 'state capacity', in determining societal outcomes. A number of countries - including the United States - have been more severely affected by the pandemic. The public health emergency in the US becoming something almost partisan, reflecting wider societal splits and ultimately more limited state capacity than one may have expected from what was the leader of the world economy and world economic policy for much of the last century.

In Ireland, policymakers were tested in many ways. Only a few years ago, statisticians here devised GNI*, a measure of domestic economic activity that is more robust to the vagaries of multinational corporations than the more standard GDP measured in use around the world since the 1930s. This year, they had to develop a new measure of unemployment - as the standard definition involves searching for work in a way that simply made no sense in a society where entire sectors have been closed down by regulation.

This new measure of unemployment peaked at an extraordinary 30% in April and - as of September 2020 and before what looks like a new wave of restrictions associated with a second wave - was still as high as 15%, three times the unemployment at the start of the year.

For all its complexity, the housing market ultimately reflects forces of supply and demand. Many - arguably most - of the commentaries I have written for the Daft.ie Report over the last decade have focused on the supply-side and its inadequacy. When it comes to demand, it is really the previous decade - the 2000s - that shows the link between household employment and the housing market.

Across both sale and rental markets, setting aside supply, the single best predictor of changes in housing prices is the unemployment rate. Where it rises - and thus when household income and net migration fall - the price of housing falls.

But not this time.

The figures from this latest Daft.ie Report, covering the sales market, show a notable bounce in the listed price of housing across Ireland in the third quarter of the year. Prices had fallen by an average of almost 2% nationwide in the second quarter of the year. Coupled with falls in the second half of 2019, as supply improved, this meant that prices were almost 4% lower, year-on-year - the largest annual fall in sale prices since early 2013.

In the third quarter of the year, however, prices rose by an average of 4.8% in just three months. This is the largest quarterly increase in average prices since the start of 2015 and the fourth largest three-quarter jump overall, in a series extending back to the start of 2006.

That prices are rising at a time of severe economic dislocation undoubtedly reflects the uneven economic impact of covid19. In Ireland as in other countries, it is certain sectors - whose workers are disproportionately renters - that have been most affected. On average, those with a greater number of years of formal education - especially where they work for larger employers - have, if anything, benefited from the dislocation. Unable to spend on hospitality and other services, aggregate household savings in Ireland have soared by over €7bn since the start of the pandemic.

Mixed in with this is the salience of your home when you are stuck in it for months on end. Figures published by Zillow last month, covering the US, don't seem to support that idea there - with urban and suburban prices rising month-on-month while rural prices fall.

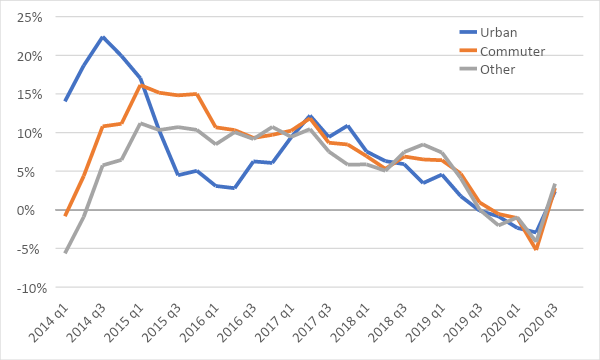

In Ireland, there is similarly no support yet for the prediction that more rural or larger properties have seen their relative price increase since the start of the year. The figure below shows annual inflation across three broad regions of the Irish housing market: the five main cities, their commuter counties (Dublin's four plus the non-city parts of the other four counties), and the rest of the country. While the trends did differ in 2014, 2015 and 2016, the three regions of the country have shown very similar patterns since - including the bump in prices reported for this quarter.

The same is true if we look at relative prices by size. The discount for a one- or two-bedroom property, or the premium for a four- or five-bedroom property - compared to a three-bedroom home and controlling for other features including location - is largely unchanged in recent months. Comparing the third quarter of 2019 and 2020, the discount for a two-bed home is 16%, all else equal, while the premium for a five-bed home is also unchanged at 55%. The discount for a one-bed is up slightly (30% to 33%) but the premium for a four-bed relative to a three-bed fell in the same 12-month period (from 44% to 42%).

The return to price growth in Q3 suggests that the disruption wrought by Covid-19 on the market as a whole was relatively short-lived. These regional and by-size figures further suggest that - so far at least - Covid-19 is not reshaping preferences either.

Given all that, it is back to supply, supply, supply. The ultimate reason prices are rising again is that there are simply not enough homes in the country, given the population and its demographics. Supply on the market on October 1st was the lowest in over 14 years - since September 2006. Covid-19 should not distract policymakers from the importance of ensuring enough new homes are built in the coming years and decades.

2nd Content Header

3rd Content Header

Written by Ronan Lyons

Source https://www.daft.ie/report